What doesn’t much matter to private equity firm, according to an anonymous survey of fund managers by Harvard Business School researchers? Financial theory, manager projections, and the talent acquired through portfolio companies.

Asset owners looking into firms’ actual strategies would do better to consider executives’ backgrounds, firm size, and even their own interactions with the organization.

Firms' valuation methods showed “deviation from what is typically recommended in finance research and teaching.”

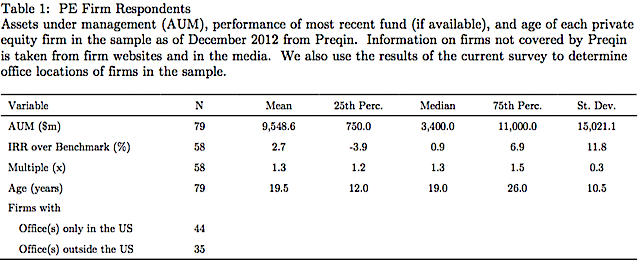

Senior staff at 79 private equity firms responded to the anonymous survey, conducted from late 2011 to the winter of 2013 by Paul Gompers, Vladimir Mukharlyamov (both of Harvard), and Steven Kaplan from the University of Chicago. The firms represented in the working paper presenting their findings had an average $10 billion under management. The vast majority focused on buyout (90%) and growth equity (75%) strategies, with many executing both.

The paper's conclusions suggested industry practices driven more by art and advertising than science.

Firms’ methodologies for capital structuring, hurdle rates, valuations, exit multiples, and internal rate of return (IRR) analysis showed “deviation from what is typically recommended in finance research and teaching,” according to Gompers, Kaplan, and Mukharlyamov.

For example, “few private equity investors use the capital asset price model (CAPM) to determine a cost of capital. Instead, private equity investors typically target a return on their investments well above a CAPM-based rate.” Firms also reported adjusting target IRRs based on disparate factors. “Hence,” the authors noted, “it seems likely that private equity firms will have different target IRRs for the same deals.”

One third of those surveyed reported advertising a net internal rate of return to investors that was on par with or higher than the median pre-fee target.

PE firms founded by former investment bankers or CFOs were more likely to favor financial engineering over operational improvements.

Out of 64 respondents who answered the question, 34.3% said they market a net IRR of 25% or more to limited partners. That projected return—25%—was also the average firm’s own targeted gross IRR. Small firms tended to project higher returns than their better-capitalized counterparts, with 40.6% advertising net IRRs of 25%-plus.

In reality, private equity funds overall posted a net 15% IRR for the three years ending June 2013 and 10-year returns of 21.7%, according to Preqin data.

A more reliable indicator of what a private equity firm has in store may be principals’ backgrounds.

“Private equity firms founded by financial general partners”—former investment bankers or CFOs, for example—“appear more likely to favor financial engineering and investing with current management,” the researchers found.

In contrast, those with purely private equity backgrounds showed the greatest commitment to operational engineering. “They are more likely to invest with the intention of adding value, to invest in the business, to look for operating improvements, to change the CEO after the deal, and to reduce costs.” The authors cautioned that their findings about the link between career experience and strategy were “rather preliminary,” and called for further study.

Asset allocators can also draw inferences about manager tendencies from age and firm size, the study suggested.

Respondents overall ranked investor pressure as the least important factor in deciding when to cash out a portfolio holding, while achieving operational goals came in first. Young managers and those working for large firms, however, gave more weight to limited partners’ (vocal) desires for redemption. Less than half (43.3%) of the respondents categorized as “old” cited investor pressure as a factor in exit timing, whereas more than two-thirds of youngsters considered it.

Finally, the authors acknowledged the possibility that respondents were not wholly candid in answering their 92-question survey, despite assurances of anonymity. Patterns in the data, however, indicated otherwise.

“While the private investors may have some incentives to shade their survey answers in some areas, particularly regarding deal sourcing and growth, the answers they provided do not give us strong reasons to believe that they acted consistently on those incentives.”

Read Gompers, Kaplan, and Mukharlyamov’s Harvard Business School working paper “What Do Private Equity Firms Say They Do?” in its entirety.

Related Content: Bain: Private Equity’s Success Could Be its Investors’ Downfall; PE’s Soaring Valuations; Rampant Deal-Making