(January 16, 2013) – Democratic and Republican politicians in the United States are truly meeting in the middle on one thing, although they may not realize it: state pension funding.

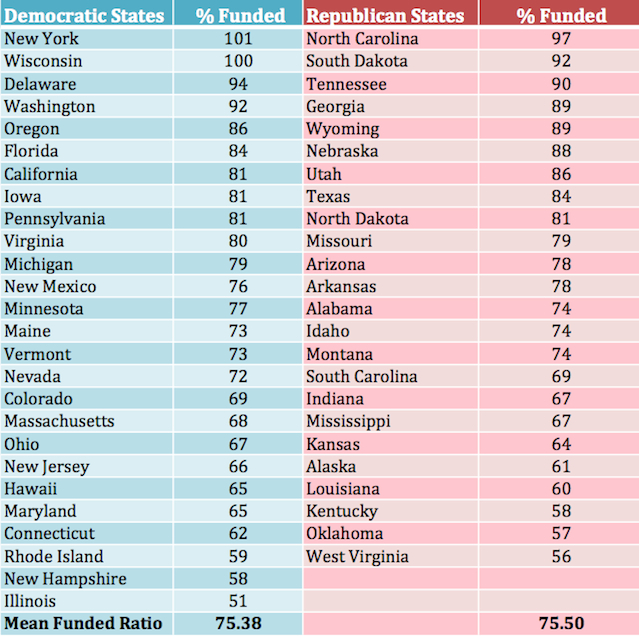

The average funded ratios of statewide public plans are almost identical for red states and blue states. The 26 states that went Democratic in the 2012 election, including major pension/population centers like New York and California, have an average of 75.38% of their liabilities funded. The 24 Republican states average 75.5% funding—a spread of just 12 basis points.

The Pew Charitable Trusts published state-by-state funding ratios in a recent report, using annual report data and actuarial valuations. The mean funding ratios are unweighted and calculated with these figures.

The most- and least-funded states both voted to elect the Obama/Biden ticket last year: New York (101%) and Illinois (51%). That said, the country’s single worst-funded public pension system, at 24.5%, is the employees’ retirement system in Kentucky—a Republican stronghold.

A number of nonpartisan factors contribute to the aggregate underfunding, and variance between different states, and fiscal discipline is a primary one.

Some municipal and state administrations pay their contributions in full, on time, and every time they’re due. Others have taken extended “contribution holidays,” including Pennsylvania and New Jersey, which went Democratic in the presidential elections but is led by a Republican, the very popular Governor Chris Christie. A few cities in California are in bankruptcy, and currently being pursued by the state retirement system for missed payments.

Governments of both leanings have raided their pension funds to make infrastructure investments, or even just make payroll. Yesterday, Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner announced that the federal government had begun dipping into the US federal employee pension fund to pay its bills while Congress debated increasing the $16.4 trillion debt limit.

Investment return assumptions also impact a state’s funded status, and do not follow partisan lines. Higher expected returns decrease unfunded liabilities, but 8%+ expectations no longer seem as sound as they once did. CIOs of funds in Republican and Democratic states alike have made the decision and often taken legislative steps to lower their funds’ assumed return rates, lowering funded statuses but potentially improving their credit ratings. Steven Grossman, former chairman of the Democratic National Committee and head of Massachusetts’ pension fund, cut the assumed rate from 8.25% to 8% last year, arguing the move would reflect well on the state’s debt issuances.

Likewise, in August, the Indiana Public Retirement System became the first among the 126 largest public retirement systems to lower its expected return below 7%, as monitored by the annual Public Fund Survey. “The risks and consequences of assuming a too high rate of return justify a conservative approach to this and other actuarial assumptions,” said the fund’s Executive Director Steve Russo at the time. “While many states have struggled to make necessary contributions to their pension funds, Indiana is in an enviable position due to the strong financial discipline of state officials and lawmakers.”