“Be nervous, county taxpayers and pensioners—very nervous,” warned local newspaper U-T San Diego’s editorial board in August 2014. Just four months before the op-ed was published, the now-$10.6 billion San Diego County Employees Retirement Association (SDCERA) had begun a “scary new chapter.”

Its outsourced-CIO Salient Partners introduced risk parity into the portfolio.

The editorial called SDCERA’s 20% risk parity allocation “difficult to swallow.” The strategy involved leveraging assets—“an aggressive investing tactic that is loved by hedge funds and disdained by such investment experts as Warren Buffett and by pension funds in general.” Furthermore, U-T San Diego had doubts about Houston-based Salient, its leader Lee Partridge, and their reported track record. It said SDCERA’s returns over the three and five years ending September 30, 2013—having hired Salient as its main strategist in 2009—were “only 84th out of 100 comparable funds.” According to Wilshire, SDCERA ranked in the 64th percentile over the three years and 73rd over five years ending September 30, 2013.

The paper argued that adding what it thought was an even riskier strategy on top of these numbers could make matters worse. “It could work out well if Partridge has a great run in picking investments—a much better one than he’s had to date,” the editorial board wrote.

To these claims, Salient has consistently responded that it has successfully placed SDCERA “as a top-performing public pension plan in the country” and said it generated a net annualized return of 9.42% over the last five-and-a-half years, exceeding the plan’s 7.75% target return.

Yet matters somehow got even worse at SDCERA. Dissatisfied with their risk parity portfolio’s relative underperformance to rallying equities, trustees developed doubts about the newfangled strategy. On May 21, 2015, SDCERA hired an internal CIO, sidelining risk parity, Salient, and Partridge—and further entrenching the risk parity market’s status quo.

The risk parity space isn’t like large-cap equity, where investors have hundreds of strategies to choose from. As of 2015, there are just 10 to 12 firms running risk parity products. And, according to consultants, the biggest and oldest names in the business have already scooped up most of the mandates. (Salient, born in 2003, managed $2.48 billion in its risk parity fund as of the end of 2014.)

“Investors tend to gravitate towards the big players in risk parity largely because of their name and legacy,” says Matt Maleri, partner at Rocaton Investment Advisors. “Bridgewater, for example, is credited with founding the strategy and has had a risk parity fund since the mid-’90s. With a long track record like that—and an institutional pedigree—it was able to enjoy a first-mover advantage, gaining both investors’ confidence and assets.”

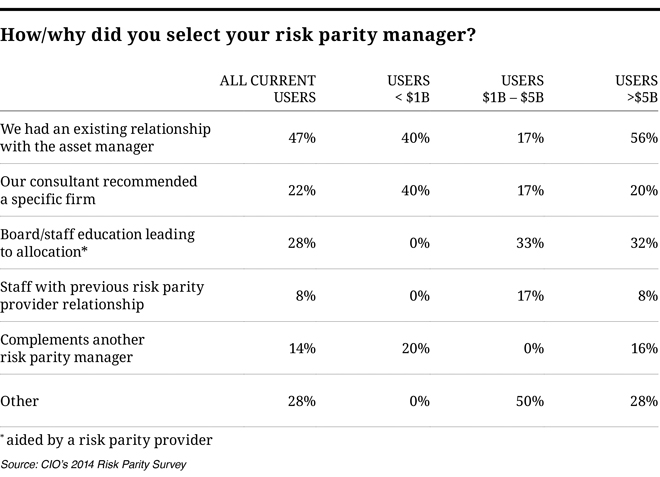

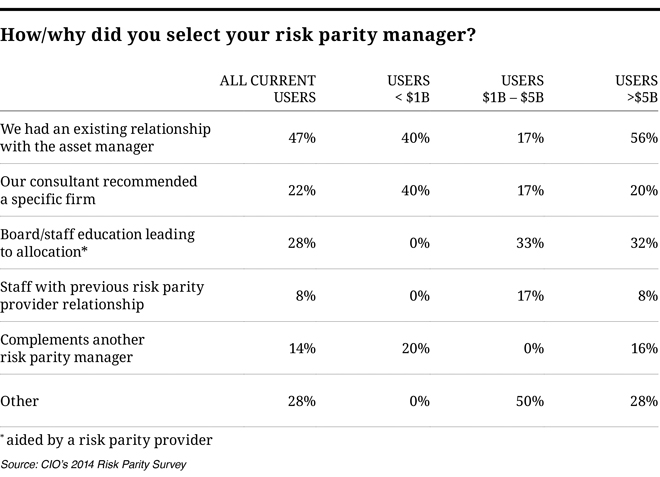

Since launching the All Weather strategy in 1996, Bridgewater has continued to build out its legacy as the Godfather of risk parity, and reportedly had $82 billion in the fund as of end of 2014. Clients also told CIO’s 2014 Risk Parity Survey that their existing relationship with the hedge fund giant largely convinced them to allocate to All Weather. The Westport, Connecticut-based firm also won their clients over with service: Some three-quarters of Bridgewater’s respondents said the company’s client service deserved a five out of five.

AQR’s risk parity strategy—with $30 billion as of December 2014—is also quickly becoming prominent since launching 10 years ago. It is slightly more dynamic than Bridgewater’s traditional passive approach, using tilts to move in and out of assets. (Bridgewater also recently launched a more dynamic risk parity product alongside All Weather—its Optimal Portfolio fund—that has reportedly brought in billions of dollars in a short amount of time.) AQR also benefits from its legacy as an alternatives manager, with clients pointing to their existing relationship in deciding to invest in its risk parity fund. In addition, nearly a third of the survey’s respondents said their advisers had recommended AQR, illustrating how the firm is becoming not only a favorite among asset owners, but also consultants.

The list of big dominating firms goes on. According to Morningstar, Invesco, Wellington, and Columbia are among the top names dwarfing the next echelon of products in size.

This oligopoly bears bad news for newer risk parity shops. The root of the problem, says Maleri, is that investable assets in risk parity are finite—and so are ways for providers to think outside the box.

“There has already been a lot of creativity in the market—some strategies are pure parity, by-the-book, and passive, while others are more tactical in nature, perhaps with an overweight on growth,” he continues. “The list of asset classes included in these strategies is also exhausted, making it difficult for firms to differentiate themselves from one another.”

Even if newer firms are able to create a fresh product that could stand out among the Bridgewaters, the Wellingtons, and all others in between, they could run into hesitation and doubt from investors. “It also may be more difficult for asset owners to get comfortable with the new players, particularly since risk parity often involves using derivatives and leverage,” Maleri says.

Many may be uncomfortable with such complex investment vehicles, as seen by U-T San Diego’s statements. But according to Bridgewater, once investors become used to looking at leverage in a “less black-and-white way—‘no leverage is good and any leverage is bad’”—they become more accepting of its use as an implementation tool.

“A moderately levered, highly diversified portfolio is less risky than an unleveraged, undiversified portfolio,” the firm wrote in an article on All Weather’s origin story. “If you can’t predict the future with much certainty and you don’t know which particular economic conditions will unfold, then it seems reasonable to hold a mix of assets that can perform well across all different types of economic environments.”

The question remains, for smaller and newer firms without Bridgewater’s gravitas, how do you convince potential clients that you’re capable of handling these tools? Rocaton’s Maleri says younger shops that are able to show a history, a track record, or a legacy running products with derivatives and leverage could have an edge—enough to break in and compete with the big dogs. There could also be opportunities to win mandates once larger funds soft- or hard-close, he adds, and assets trickle down to smaller firms.

“There are so many flavors and philosophies when it comes to risk,” says Kristin Reynolds, partner at NEPC. “Managers have to consider how clients are thinking about structuring risk in their portfolios. There are strategies across the gamut. A few years ago, the trend leaned towards dynamically allocating, but more recently, there has been a push towards an equal risk profile with dynamic and tactical allocations underneath that. The key is to find a niche that will appeal to asset owners and their needs.”

Reynolds adds that there are a handful of institutional portfolios moving towards risk parity on a total fund level, much like the innovators at the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and State of Wisconsin Investment Board. With the first leg of the first-mover advantage already past, perhaps newer shops can compete alongside the powerful elite with their own personal selling point: diversification.

Note: An earlier version of this article misstated SDCERA’s risk parity allocation (as of August 2014) and Salient’s risk parity assets under management. It has been updated with the correct figures.