Inflation hedgers, you’re screwed.

“On an aggregate level, it is impossible fully to hedge liabilities,” according to Mercer Principal Phil Edwards, who sums up a major problem facing pension funds across Europe: There is a massive shortage of inflation-linked assets.

In the UK, index-linked gilts—which are key to asset-liability matching strategies—make up roughly 25% of the country’s currently issued government debt. The demand for inflation-linked assets has driven yields to record lows, to the point that investors are willing to accept an almost guaranteed loss in real terms to hedge against rising prices.

Fathom Consulting—which is fast becoming CIO’s go-to provider of bad economic news—estimated last year that, to meet demand, the UK would have to triple the portion of its issued debt linked to inflation.

This is not going to happen. In its 2015/2016 report, the UK Treasury said index-linked issuance would actually fall in the coming financial year. The UK’s declining deficit is also likely to reduce the country’s need to put out new gilts.

This threatens to leave defined benefit plans “substantially exposed to unexpected changes in inflation,” Fathom wrote in its 2014 report “Who Carries the Risk?” This could have “major implications for the solvency of individual schemes and their sponsors, and by extension for the Pension Protection Fund” (PPF). As a lifeboat for bankrupt company pensions, the PPF may end up absorbing a good deal more inflation risk than it does now. Fathom warned of potential for benefit restrictions, which the PPF can enforce if a pension’s funding level is particularly low when it is transferred to the rescue fund.

In Europe, only France, Italy, and Germany have sufficiently large index-linked bond markets to cover the hedging need. These too have been in high demand, with yields falling in the past few years as prices have risen. With central banks more concerned about deflation than inflation, there is not much appetite to issue more. The US has a deep market, but only if you are willing to take on substantial currency risk alongside the possibility that inflation runs at a different rate to your own.

“There are not enough index-linked gilts—you have to buy other assets to meet your liabilities,” says Edwards, Mercer’s European director of strategic research.

So where else can asset owners go?

That is the great “unanswered question” for Edwards—and many asset owners besides. In truth there are a variety of answers, but each one is unsatisfying and flawed.

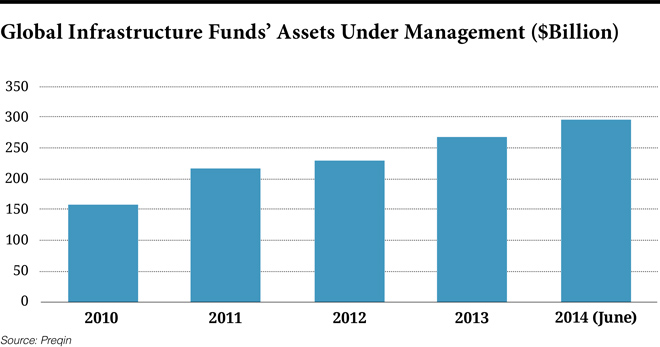

The recent rise of infrastructure investing in Europe has been linked to a desire among some investors for inflation protection. Last year saw €7.5 billion raised by 15 European-focussed funds, according to data provider Preqin, and funds themselves are being scaled up as well. The average new European infrastructure fund closed after raising €500 million last year—a 14% rise on the 2013 figure and more than double the 2012 average.

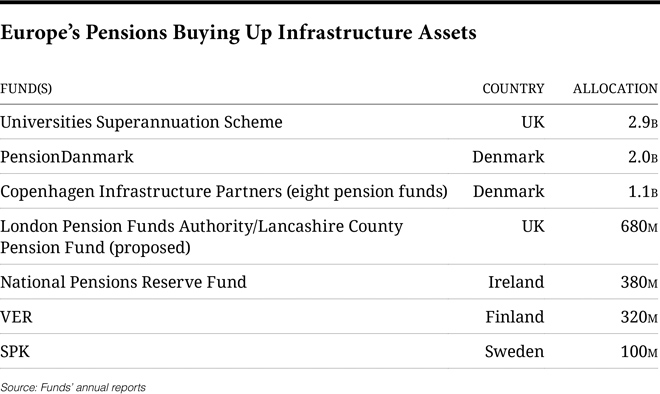

In addition, pensions in Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, and the UK are pooling resources to buy infrastructure. These deals, by and large, cut out fund managers so institutional investors purchase assets directly in an attempt to reduce costs and increase control over their portfolios.

But are the assets there? Fathom Consulting’s calculations indicate that, even if the UK government were to sell the majority of state-owned assets to private investors, the overall gap would not be close to covered.

Fund management giant M&G Investments has warned that infrastructure debt is becoming a crowded trade: Co-head of Alternative Credit William Nicoll said last year that he could “quite happily fill a room with people wanting to buy infrastructure debt, but there is not much of it around and it’s quite expensive”.

The demand story is the same for property. Unlisted real estate funds had an aggregate $742 billion (€683 billion) in assets under management at the end of 2014, according to Preqin, the highest level on record. Rental incomes’ links to inflation are undoubtedly an attractive feature for many institutional buyers, but in areas such as London, yields have also fallen to record lows as demand soars.

Mark Gull, head of fixed income at Pension Insurance Corporation, has also cast doubt on the capacity of asset classes such as infrastructure to meet the liability-hedging demands of investors. “I would love to say more infrastructure projects are coming along, but the size of these is pretty small in the context of the index-linked gilt market,” Gull says.

However, one infrastructure investor at a large European pension fund says inflation hedging should not be the primary driver of an allocation to the asset class.

“I would love to say more infrastructure projects are coming along, but the size of

these is pretty small in the context of the index-linked gilt market.” —Mark Gull“If someone tells you infrastructure offers

perfect inflation protection, it is just not true,” she proclaims. “Infrastructure

has certain hedge qualities in that, if inflation is higher, infrastructure

tends to increase in price and have higher cash flows.” But that is not always

going to be the case—particularly if inflation gets too high.

In addition, infrastructure is a very broad asset class, taking in everything from oil pipelines to ports, toll roads, and electricity distribution networks. Not all of these—in fact, very few—offer direct links between pricing and inflation.

“On average you are better protected against inflation if you are invested in fixed income,” says the infrastructure investor. “If inflation hedging is the only reason you’re considering infrastructure, then you’re missing the point.”

There is another way. In November last year, UK’s TRW Pension Scheme took a novel approach as part of a major de-risking project featuring a £2.5 billion (€3.4 billion) pensioner buy-out backed by Legal & General. The fund offered members a “pensions increase exchange”, which effectively increases the annual amount promised to each retiree from the defined benefit plan but removes any indexation. In other words, TRW paid members to take on the inflation risk.

UK pension funds made a record number of these offers in the 2013/2014 financial year, according to Towers Watson. This number is only set to increase as defined benefit funds seek ways to reduce their exposure to inflation risk—and innovation should rocket as a result.