Art by Ji Hyun YuOur daily lives are driven by

trends, some of which become meaningful and permanent changes. Others, not so

much.

Art by Ji Hyun YuOur daily lives are driven by

trends, some of which become meaningful and permanent changes. Others, not so

much.

What once seemed out of the ordinary, or even unimaginable, quickly becomes the norm (mobile phones), while something that seems on everyone’s to-do list disappears overnight (who still collects firewood?).

It’s an investor’s job to tap these trends, or even pre-empt them, and they should make a fortune. Shouldn’t they? In fact data shows what plays out in our lives has little impact on investment. It is us, ourselves, who are the most important factor to consider when investing—not our foibles and fancies.

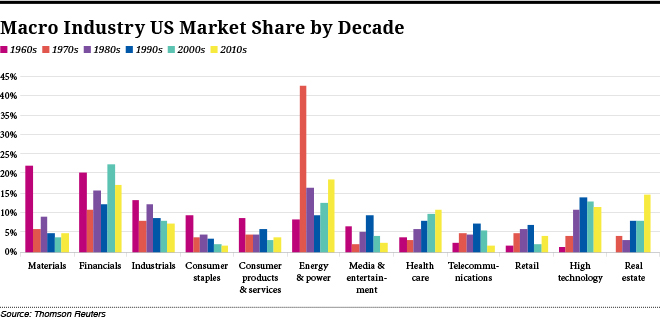

As the summer of love was spreading its glow through the 1960s, very un-hip stocks drove equity markets. Materials made up the largest stakes in the US—the world’s biggest market—while financial companies followed close behind, according to Thomson Reuters data. While the cult of television and entertainment swept through developed nations, this sector’s value was less than half as important to financial markets as heavy industry.

So far this decade, financials are proving the boom stock as they recover from the crisis, beaten only by energy and power, despite the commodity rout witnessed over the past two years. Smartphones and high tech stocks? Only fourth in line after the aforementioned sectors, with real estate coming in third. Media and telecoms? Despite us spending an increasing amount of time looking at or interacting with others via these sectors’ companies, they amount only to 4.7% of overall market share.

Investing in what your friends and family like will not get you rich—or your pension to full funding—but how important is considering sectors and industries when selecting equities? Research published by the London Business School suggests they are very important—but often overlooked.

In their latest annual “Triumph of the Optimists” report, Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh, and Mike Staunton explain how industries are a risk factor that many have decided to omit. They go as far as saying it has become a non-priced investment factor, even though it should still pull an investor’s attention—albeit with a twist.

When we talk about ‘high tech’ stocks, we think of microchip manufacturers, internet service providers, and data storage facilities. In the 1900s, there were high technology stocks too—except telegraphs were the iPhones of the day and messenger boys were the equivalent of WhatsApp. Shipping lines have been replaced by airlines, ice boxes by fridges, and let’s not forget the canal boom and bust with the advent of rail cargo transportation.

Yet Dimson, Marsh, and Staunton warn that while it is possible and useful to pick out trends of the past and import them to contemporary markets, using them to make a cookie cutter for the future is fruitless.

Emerging markets have traditionally taken on many of the industries as developed economies move on, but they engage with these sectors differently. Disruptive technologies such as the internet have the power to be major market game changers, just as the railroads once were.

It is the actual investor—and their fellow man—that is the most important in any discussion on how demographics affect industries and their worth.

“People misrepresent and misunderstand data as they assume every generation is like the one before,” says Dr. Amlan Roy, head of global demographics and pensions research at Credit Suisse. “In fact, each generation has changed. A 60-year-old today is not the same as a 60-year-old 50 years ago, yet many continue to count the number of people—and that is not right.”

Think about it. Did your mother walk or was she driven to school? Did your father spend his pocket money on milkshakes and skateboards or an Xbox? Your family members are (probably) all citizens of the same country and therefore considered and counted in the same manner—and there lies the biggest fault made by investors and prospectors, says Roy.

“Investors have to understand demographics in terms of consumers and workers, not just people,” he says.

Consider the female workforce. Since the 1960s, women’s education levels, participation in work, and salaries have all rocketed while their time in the home has fallen.

Internet-based commerce has soared, but don’t think kids are leading the charge. Some of the highest growth has come from the 55-to-74 age bracket, Roy’s data show.

Young people are staying in education later and no longer working at the same jobs for decades. They have different skills, consumption patterns, and career ambitions.

“Even within the same age categories there are significant differences,” says Roy. “For example, an 80-year-old living in the UK costs the state probably 60% to 70% more than a 65-year-old, yet they are often grouped in the same ‘old age’ category. It is the same for how people consume: expenditure patterns vary depending on age, gender, wealth, education, skills, family structure, etc.”

And if you think things vary within age groups, consider countries. A 21-year-old in Chennai likely has a different day-to-day than someone the same age in Atlanta. A 45-year-old in Addis Ababa will have a completely different attitude to earning and saving than her counterpart in Melbourne.

“Investors don’t often appreciate what the data tell them,” says Roy. “They have to consider the next five to ten years and understand that demographics are different all around the world. GDP growth is affected by workers and these workers are not the same in each country. Investors have to consider productivity, wages, and how workers spend and save. These are the nuances of finance.”

And these nuances combine to make a mockery of some of the standards of finance, according to Roy—and many others in the industry.

“Asset allocation theories that were taught by finance professors in the 1980s—the capital asset pricing model or Markowitz’s portfolio theory, for example—are no longer valid,” says Roy. “There is no longer a risk-free asset and no consensus on a market portfolio either.”

Hindsight may be 20/20, but you’ll need more than perfect vision to look into the future.